An Intuition

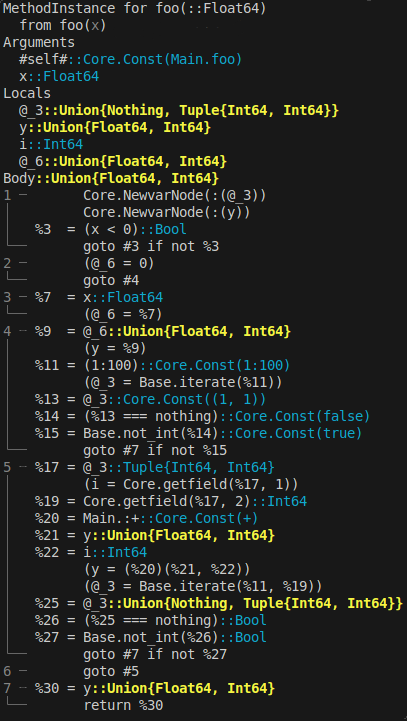

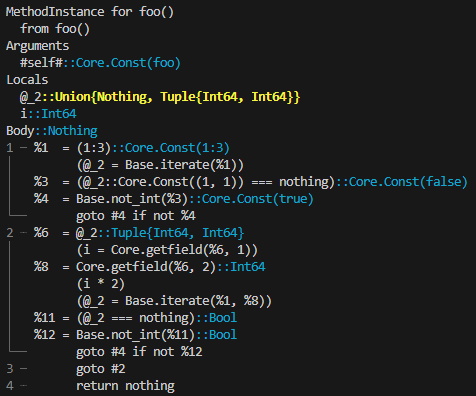

When a function is called, Julia follows a well-defined sequence of steps to determine how that call should be executed. We already described this process and now briefly review it.

Consider a function foo(x) = x + 2 and the execution of foo(a) for some variable a. We assume a has a specific value assigned and therefore a concrete type, although we omit explicitly specifying a value for a. This lets us highlight that the process unfolded depends on types, rather than values.

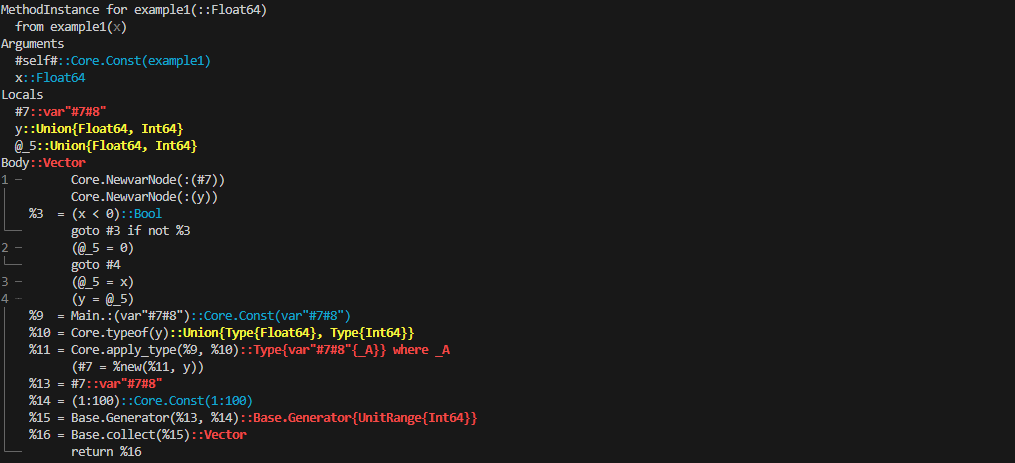

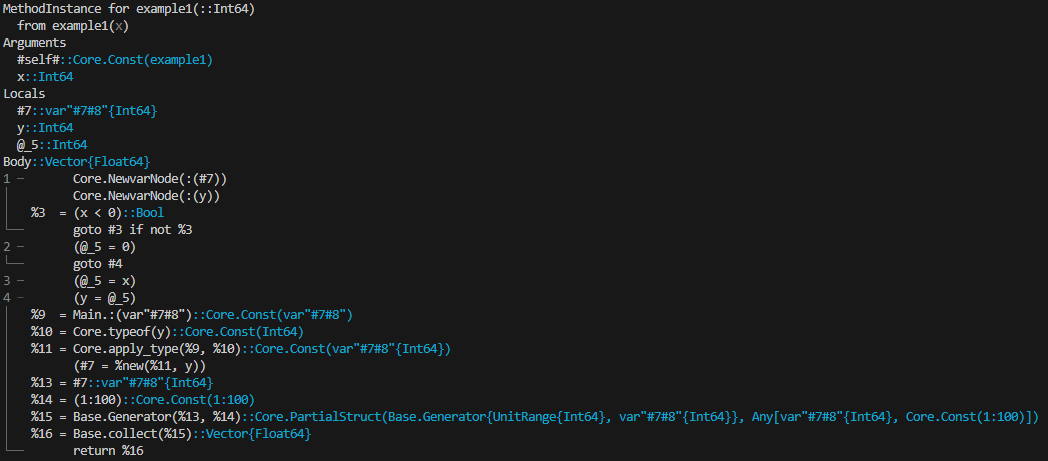

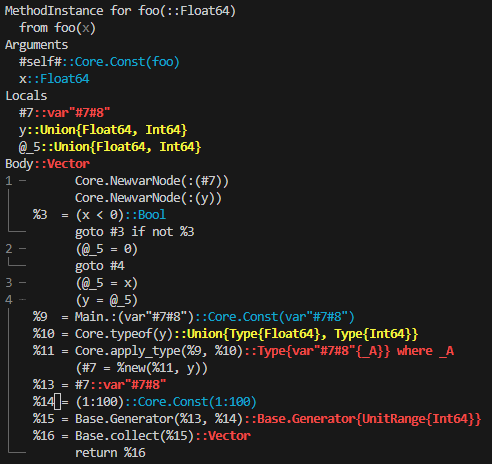

When evaluating foo(a), Julia first determines the concrete type of a, which we'll denote as T. It then checks whether a compiled method instance of foo specialized for an argument of type T already exists. If such an instance exists, then foo(a) is executed immediately. Otherwise, Julia proceeds to compile one. This compilation step leverages type inference, wherein the compiler attempts to deduce concrete types for all terms within the function body. The resulting machine code is then stored, making it readily available for subsequent calls of foo(b) with b having type T.

Type Stability and Performance

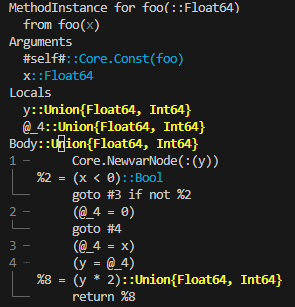

The key to generating fast code lies in the information available to the compiler during the compilation stage. This information is primarily gathered through type inference, where the compiler identifies the specific type of each variable and expression involved. When the compiler can accurately predict a single concrete type for the function's output, the function call is said to be type stable.

While this constitutes the formal definition of type stability, a more stringent definition is usually applied in practice: the compiler must be able to infer concrete types for each expression within the function, not only for the final output. This definition aligns with the output provided by @code_warntype. This is the built-in macro to detect type instabilities, which we'll present in the next subsection.

When type stability holds, the compiler can specialize the computational approach for each operation, resulting in fast execution. Essentially, type stability dictates that there's sufficient information to determine a straight execution path, thus avoiding unnecessary type checks and dispatches at runtime.

In contrast, type-unstable functions generate generic code, thus accommodating each possible combination of concrete types. This results in additional overhead during runtime, where Julia is forced to dynamically gather type information and perform extra calculations based on it. The consequence is a pronounced deterioration in performance.

Type Stability Characterizes Function Calls

Type Stability Characterizes Function CallsIt's common to describe a function as "type stable". Strictly speaking, however, type stability isn't a property of the function. Rather, it's a property of how the function behaves when called with arguments of particular concrete types. The distinction is crucial in practice, since a function may exhibit type stability for certain input types, but not for others.

Home

Home Chapters

Chapters Links

Links BOOK in PDF

BOOK in PDF